Magic Numbers in Nuclear Physics

Magic numbers are one of the key organizing principles in nuclear physics. They explain why certain nuclei are exceptionally stable, much like noble gases in atomic chemistry.

What Are Magic Numbers?

In nuclear physics, a magic number is a number of protons or neutrons that completes a nuclear shell, producing an unusually stable nucleus.

The experimentally established magic numbers are:

![]()

A nucleus is doubly magic if both proton number ![]() and neutron number

and neutron number ![]() are magic.

are magic.

Examples of Doubly Magic Nuclei

| Nucleus | Z | N | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4He | 2 | 2 | Alpha particle |

| 16O | 8 | 8 | Very stable |

| 40Ca | 20 | 20 | Stable |

| 48Ca | 20 | 28 | Neutron-rich, stable |

| 132Sn | 50 | 82 | Radioactive but long-lived |

| 208Pb | 82 | 126 | Most famous doubly magic nucleus |

These nuclei show:

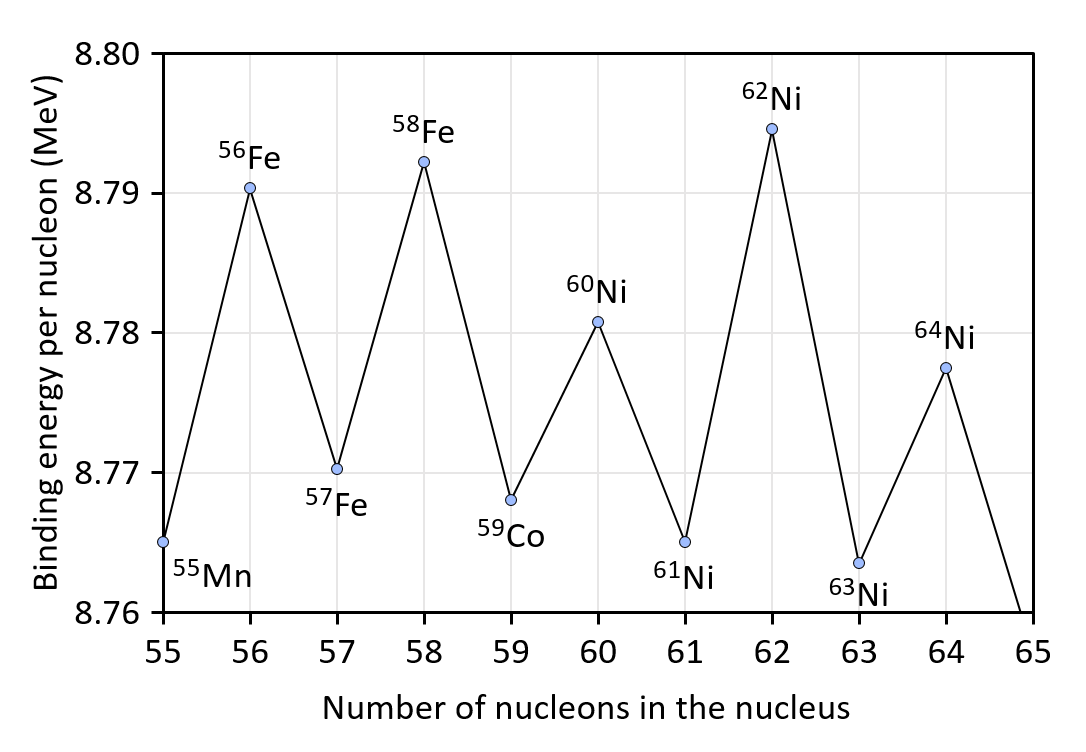

- Higher binding energy per nucleon

- Longer half-lives (often stable)

- Lower reaction cross sections

- Reduced deformation (more spherical)

Why Do Magic Numbers Exist?

The Nuclear Shell Model

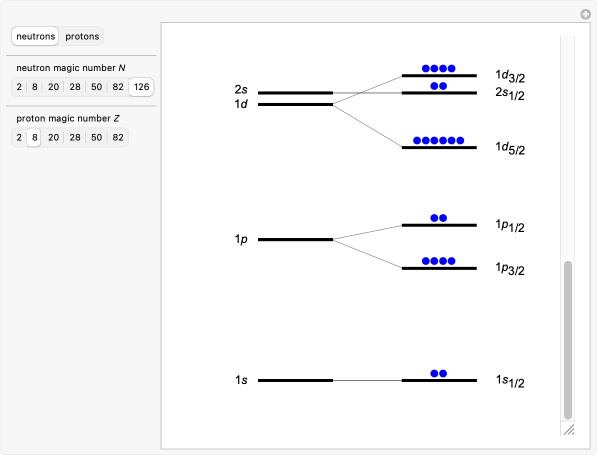

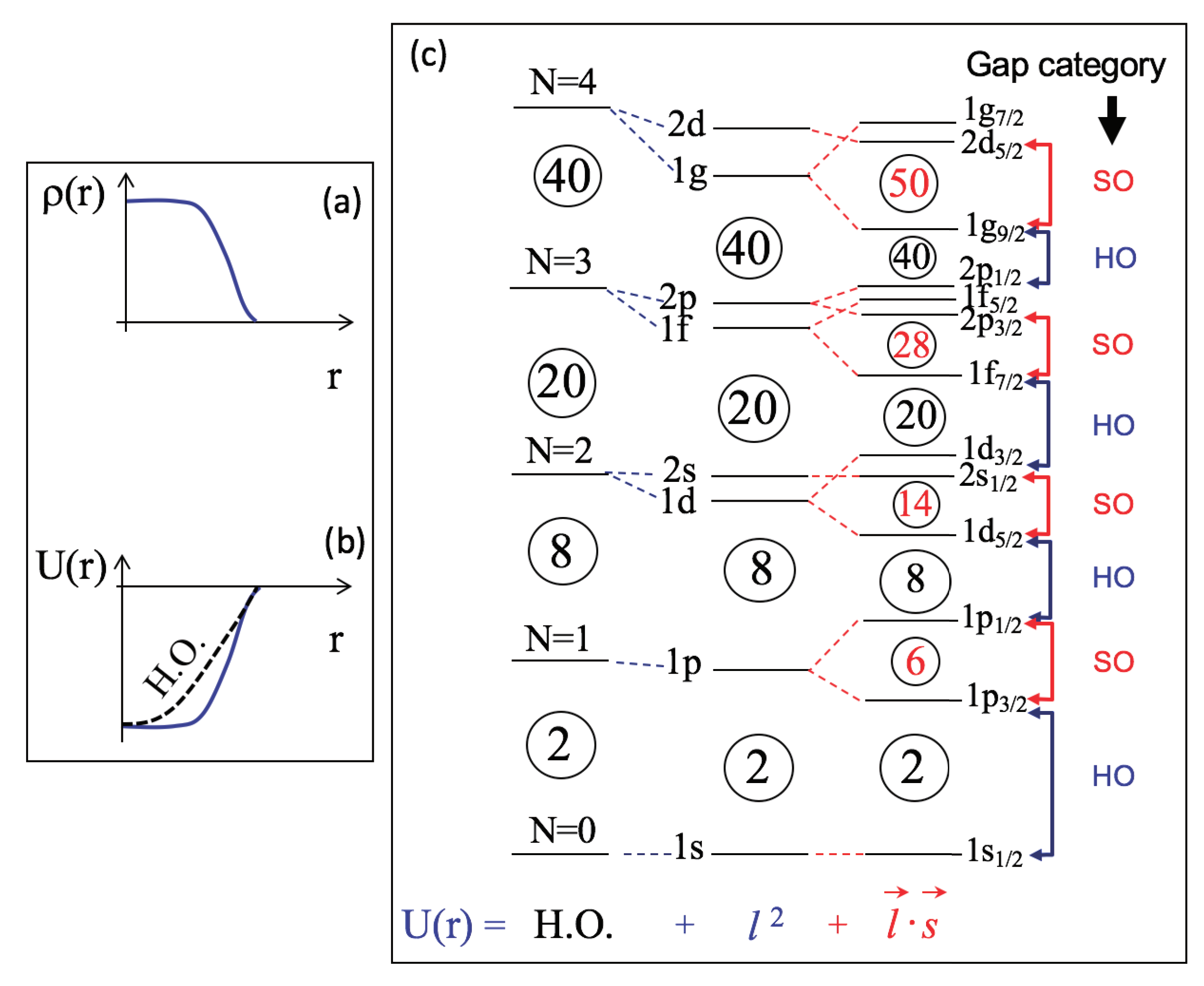

Magic numbers arise from the nuclear shell model, in which protons and neutrons move in quantized energy levels inside an average nuclear potential, somewhat like electrons in atoms.

However, the nuclear potential is:

- Short-range

- Strong

- Includes spin–orbit coupling, which is crucial

The Key Ingredient: Spin–Orbit Coupling

Without spin–orbit interaction, shell closures would occur at:

![]()

These do not match observations.

When a strong spin–orbit interaction is added:

![]()

Energy levels split strongly depending on whether the nucleon’s spin is aligned or anti-aligned with its orbital angular momentum.

This splitting rearranges energy gaps, producing the observed magic numbers:

![]()

This was a major triumph of nuclear theory in the late 1940s (Mayer & Jensen).

Observable Consequences of Magic Numbers

- Stability: Higher separation energies, reduced decay probability. Example: 208Pb is extraordinarily stable despite its large size.

- Nuclear Shape: Tend to be spherical; non-magic nuclei often deformed.

- Excitation Spectra: Large energy gaps → fewer low-lying excited states.

- Abundance in Nature: Peaks in cosmic and solar-system abundances (e.g., r-process peaks at N = 50, 82, 126).

Are Magic Numbers Always the Same?

Shell Evolution

In very neutron-rich or proton-rich nuclei, shell structure can change:

- Traditional magic numbers can weaken

- New “magic” numbers may appear (e.g., N = 16, N = 32)

This happens because of tensor forces, changes in spin–orbit strength, and modified nuclear density profiles. This is an active area of modern nuclear research.

Analogy to Atomic Physics

Atomic Physics

- Electron shells

- Noble gases

- Coulomb potential

- Spin–orbit weak

Nuclear Physics

- Proton/neutron shells

- Magic nuclei

- Strong nuclear potential

- Spin–orbit strong

Historical Note

Maria Goeppert Mayer and J. Hans D. Jensen independently explained magic numbers in 1949.

They received the 1963 Nobel Prize in Physics for the nuclear shell model.

Magic numbers are specific counts of protons or neutrons that complete nuclear shells, producing exceptionally stable nuclei; they arise from quantum shell structure shaped by a strong spin–orbit interaction in the nuclear force.

Recent Comments